Moody’s lowered the Bahrain’s long-term issuer rating to B2 from B1 and maintained a negative outlook. It has also lowered Bahrain’s long-term foreign-currency bond ceiling to Ba3 from Ba2 and long-term foreign-currency deposit ceiling to B3 from B2. The short-term foreign-currency bond and deposits ceiling remain unchanged at Not Prime. Bahrain’s long-term local currency country risk ceilings were lowered to Ba2 from Ba1.

This downgrade comes despite the announcement of a recently discovered large off-shore oil reservoir and the assumption that the kingdom’s Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) neighbors will provide some financial support, consistent with a broad statement issued on 27 June and without which Bahrain’s creditworthiness would be significantly weaker.

The negative outlook reflects the risk that financial support from the GCC is not timely and comprehensive enough to maintain Bahrain’s credit profile at B2 through a series of forthcoming debt repayments, including a $750 million sovereign sukuk repayment due on 22 November 2018. Moreover, with regards to the off-shore oil reservoir, Moody’s cannot ascertain at the current stage of exploration with any degree of confidence how much of the announced 80 billion barrels of oil-in-place could be technically recoverable and at what cost. In any case, the government does not expect oil production from the new field that would materially improve Bahrain’s fiscal and external balance to start before early 2023.

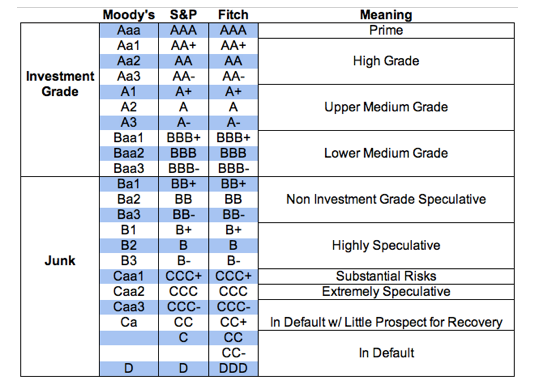

A credit rating is an assessment of an entity’s ability to pay its financial obligations. the ability to pay financial obligations is referred to as “creditworthiness.” Credit ratings apply to debt securities like bonds, notes, and other debt instruments (such as certain asset-backed securities) and do not apply to equity securities like common stock. Credit ratings also are assigned to companies and governments.

When making investment decisions, credit ratings and any related rating and industry trend reports can be helpful tools, provided they are used appropriately. Credit ratings may offer an alternative point of view to your own financial analysis or that of your financial adviser.

A downgrade to junk status is associated with high risk. Therefore, high borrowing costs. For governments it means allocating more to debt servicing costs (interest payment). Less money will be available for social grants, investment priorities, creating jobs and ultimately reducing the GDP growth potential of the country. More interest payment also crowds out other critical spending. Social services is an example. This is the main reason why a sovereign has to avoid being downgraded into a junk, or sub-investment grade.

Bahrain was downgraded to junk status by Moody’s back in March 2016 and has been sliding down the scale ever since. With this most recent downgrade it needs to go up five positions before beings considered as investment grade.

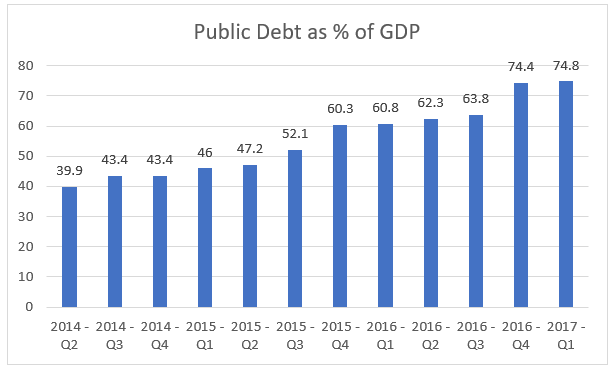

The recent downgrade to B2 reflects Moody’s view that the credit profile of the Bahraini government will continue to weaken materially in the coming years. The rating agency expects Bahrain’s government debt burden and debt affordability to weaken further significantly over the coming two to three years.

Despite a rise in oil prices, the government’s budget deficit will oblige it to constrain spending, which will moderate growth in the non-oil economy. Higher borrowing costs due to rising interest rates, and reduced subsidies will weigh on corporate and household income, putting mild pressure on loan quality. In addition, rising government debt is reducing the government’s capacity to support the country’s banks in a crisis.

Moody’s expects economic growth to slow to 2.8% in 2018 from 3.9% in 2017 as the government constrains spending, due to its large budget deficit. As a result, credit growth will decelerate slightly to 5%-7% from 8% in 2017.

Moody’s downgraded Bahrain’s issuer rating two notches from Ba2 to B1 last year despite the government’s steps towards economic reforms, including lifting some subsidies from fuel and utility tariffs, government restructuring, and increasing fees on government services. According to Moody’s, these steps were not considered to be aggressive enough in light of the financial challenges.

Yet again, the Bahraini government has not announced any new significant policy measures and Moody’s believes that the lack of new policy announcements in the face of rising liquidity pressures underscores very limited policy flexibility and weaker institutional strength than previously assessed.

The implementation of the value-added tax, originally planned for 2018, has been postponed until next year. Meanwhile, in January all new fiscal austerity measures were suspended until parliament agrees on a new system to compensate citizens for the higher cost of living implied by the measures. The most significant fiscal measure implemented this year is the excise tax on soft drinks and tobacco products, which is expected to yield around 0.4% of GDP in extra revenue. By comparison, the government expects the overall spending to increase by close to 1% of GDP.

| Country | Moody’s Long-Term Credit Rating |

| Kuwait | Aa2 |

| UAE | Aa2 |

| Qatar | Aa3 |

| Saudi Arabia | A1 |

| Oman | Baa2 |

| Morocco | Ba1 |

| Jordan | B1 |

| Tunisia | B1 |

| Bahrain | B2 |

| Lebanon | B2 |

| Egypt | B3 |

| Iraq | Caa1 |

Comparison of Moody’s Rating for Arab Countries

While Moody’s acknowledges the fact that Bahrain’s economy is fairly diversified, with non-oil sectors contributing close to 80% of nominal GDP on average since 2010, it is wary that the government shows no indication that it will use this economic base to materially diversify its revenue base to reduce its reliance on oil-related income which will continue to suffer from weak oil prices in the coming years. Non-oil economic performance will be supported by access to funding under the Gulf Development Fund. While these funds are not part of the Bahraini government’s budget, they will support the government in reducing investment expenditure without unduly harming growth.

Bahrain’s net asset international investment position, its stock of foreign assets minus foreign liabilities, which stood at 74.5% of GDP in 2016 and 87% of GDP in 2017, provides some form of external buffer. However, Moody’s expects it to decline significantly because external liabilities will increase at a much faster rate than the country’s assets. More importantly, foreign exchange reserves at the Central Bank of Bahrain are low and very volatile, covering only around one month of goods and services imports. Following a pause in the dissemination of this data in 2015, the time series disclosed by the central bank more recently shows a material decline in foreign exchange reserves over the last two years, averaging only around $2.5 billion in the first quarter of 2017.

RATIONALE FOR THE NEGATIVE OUTLOOK

The negative outlook reflects continued downside risks to the B2 rating, which manifest themselves in heightened government and external liquidity risks. Given the expected large fiscal deficits and sizable amortization payments falling due over the coming years, Bahrain’s government gross financing needs will reach more than 30% of GDP over the next two years.

The further deterioration in the government’s balance sheet, combined with continued external debt issuance from other countries in the region, will lower the supply of external funding. In addition, in light of rising global interest rates, the cost of funding will go up.

Moody’s expects that the combination of these two factors heightens the risk that finance is obtainable only at much less affordable rates for Bahrain, or potentially reduced amounts. Despite the 27 June announcement stating that an “integrated program … will soon be announced”, there has been no further communication to date, either from the Bahraini authorities or from Saudi Arabia (A1 stable), the UAE (Aa2 stable) and Kuwait (Aa2 stable).

As a result, there is a risk that such support may not be sufficient to stabilize Bahrain’s credit metrics and in particular allow the government to meet its debt obligations while avoiding prohibitively expensive costs.

WHAT COULD MOVE THE RATING UP/DOWN

Given the negative rating outlook, any upward movement in the rating in the foreseeable future is highly unlikely. Moody’s would likely change the outlook to stable if a detailed and credible announcement of GCC financial support was made and if such support raised the probability that the government would undertake comprehensive fiscal consolidation which would materially narrow non-oil fiscal deficits and stabilize its debt burden. Such a policy announcement would probably enable Bahrain to regain access to the international capital markets, diversifying its financing sources. Combined, the availability of GCC financial support and regained market access would provide some scope to rebuild the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves.

Moody’s would likely downgrade Bahrain’s rating in the event of continued deterioration in fiscal and external metrics amid a prolonged absence of a detailed announcement from the GCC countries about the group’s commitment to support Bahrain’s government and external financing needs. Possibly related, a downgrade would also likely occur if the sustainability of Bahrain’s pegged exchange rate regime was increasingly threatened.